The Practice of Music Part III

On Music Theory

Next free write: I believe in a holistic approach to compositional pedagogy that music theory and history, hearing, playing, and performing are interconnected and inform each other and are all vital to learning how to compose. This is my first attempt at articulating and organizing these thoughts so I have no idea how this will go.

To begin I want to focus on the physical playing and singing of music. There are two main areas of focus aural skills and keyboard skills.

Aural skills consist of sight singing, eventually without aid (except the first pitch of course), and being able to hear stuff like melodic intervals and harmonic dyads, chord qualities, scale types, common chord progressions, and different instruments. I think the end game of this is being able to hear music just by looking at the score and singing in a choir.

Keyboard skills itself has two distinct but overlapping areas of focus it seems: technical comfort at the instrument and the study of harmony. The first is straightforward practicing scales and arpeggios in various keys in parallel and contrary motion in increasing speeds, practicing chord progressions like certain sequential and cadential patterns in various keys and chord inversions--this also aids sight reading at the instrument. The second section refers to the skill of thorough bass, harmonizing a melody, and keyboard harmony. These disciplines help learn common practice harmonic idioms but also help develop an intuitive understanding of harmony and voice leading--this also relates to aural skills as it is the synthesis of a musicians aural and practical training.

Lastly, I am must keep in mind the 'intuitive' aspect of keyboard harmony. I do not want to unconsciously constrain my voice leading to common patterns like at modulations for example. I want to rely on my ear which will be informed by my study, not the other way around.

The first thing I want to set in stone in this section is in regard to what I mentioned above about musical style as a conversation. The Teacher, Theorist, and Composer R. O. Morris expertly articulates in the first chapter of his manual, Contrapuntal Technique in the sixteenth century (1934). “Every serious musician should have some knowledge of the history of his art, and of the manner in which his materia musica has been accumulated (3). Thus I cannot

I will be engaging heavily with the readings of Theorists. This comes with a warning:

I want to begin my practical study with the 16th century using the Roman School headed by Palestrina and the Tudor Composers as models as Morris continues “The sixteenth century is beyond all question one of the great periods of music, and its technique is quite unlike the technique of any succeeding period…Similarly a musician should not hesitate to spend a few months in mastering the idiom of the great sixteenth-century composers, for in doing so he will enlarge his mental horizon, acquire some sense of scholarship, and realize more fully the continuity of musical progress” (3).

Mini Essay II: Monophony

A musical ‘line’ is a linear series of pitches that occur one after the other, which a listener perceives as a single entity, most often referred to as a melody. When a whole or section of a piece of music contains only a single line or ‘tune,’ it is monophonic in texture (see example I). The term is derived from the Greek mono, meaning single or one, and phone, meaning sound.

Bruckner, Inveni David (WAB 19), Bars 1 - 6. Monophony (bars 1 - 2) moving to Homophony (m.3 to 5)—a common fingerprint of Bruckner.

In the Bruckner example, the doubling is at the unison and octave: the line is still perceived by a listener as a single entity because of the perfect sonority of the unison and octave interval (there is also no rhythmic differences between the voices). Therefore a piece of music may be monophonic with multiple parts.

The doubling present in example I is an orchestration of the voice. Bruckner requires the combined color of the tenor and bass choirs. Sonically, the melody or line in measures 1-2 will sound louder, generating a cohesive dynamic and vocal range within this phrase providing a smoother transition to homophony at measure 3. If Bruckner had assigned this melody to a single part, such as tenor I, the entrance of the tenor II and bass parts would likely have felt more dramatic.

One may come across the term heterophony in relation to monophony (see example II). Heterophony describes a musical texture where a ‘melody’ is realized in more than one part simultaneously where each successive voice demonstrates a varied realization of the main melody. The degree of change between the varied and original melody can be either small or large as long as the melodic contour or ‘skeleton’ of the main melody is present.

Bach, from Cantata Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott (BWV 80), bars 1 - 9. Heterophony example, found on wikipedia.

Parry - A Collection of Shorter Articles

The following articles Parry wrote are short. I decided to collect my reading of them together into one post. These articles are the last of his contributions to terms beginning with the letter ‘B.’

The Bass. Fr. Basse, Ger. Bass, Ital. Basso. Parry begins with a very general definition of this term: the lower counterpart of the “higher” treble clef in a musical system. However, this definition implies that the range of a bass part lies within the 3rd octave or lower. Parry then introduces the etymology of the term ‘bass,’ which is ultimately derived from the Greek βάσις or ‘basis.’ Parry continues, “The meaning is clearly that of the foundation or support in a musical composition by the part which is deepest in sound, and there is thus no implication as to the range in compass of such a part.” The ‘bass’ supports the harmony of a composition. For example, the lowest-sounding note in a triad, regardless of inversion or range, can be called the bass note.

Basso Continuo. In this short contribution, Parry states that the Italian term Basso continuo is the same as the English term Thorough-Bass. For some reason, I never made a connection. W. S. Rockstro (1823-1895) contributes a complete discussion under the term ‘Thorough-Bass’ elsewhere in the dictionary.

Basso Ostinato. Parry states that Basso ostinato is the Italian term for Ground-Bass, like the previous article. Here, though, he provides a definition: “the continual repetition of a phrase in the bass part through the whole or a portion of a movement, upon which a variety of harmonies and figures are successively built.” Unlike the last article, Parry contributes the complete discussion under the term ‘Ground-Bass,’ which I will get to later as I move through these alphabetically.

Benedicite. It may also be referred to as the ‘Song of the Three Children.’ It is a canticle used in the Anglican service after the first lesson/service in the morning, alternatively with the ‘Te Deum.’ Parry then synthesizes the long history of the use of this text. Lastly, Parry recommends that the' Benedicite' text is better expressed as a chant than any other musical form because the second half of each verse is the same throughout. Parry cites Purcell’s Z. 230/3 "Benedicite Omnia Opera in B-flat major" (before 1682) as an example of the ineffective use of the text.

Benedictus. It may also be referred to as the song of Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist. The text is taken from Luke I. This canticle is appointed alternately with the ‘Jubilate,’ which follows the morning services of the Anglican Church. The ‘Benedictus’ has held its position far longer than the ‘Jubilate,’ with the ‘Benedictus’ in place since ancient times and the ‘Jubilate’ being added to Cranmer’s English Liturgy in 1582 to avoid repetition when the ‘Benedictus’ text occurs in the Gospel or second lesson. It is suited for complex and elaborate forms of composition. Parry cites examples from Tallis and Gibbons. Parry also notes the same canticle is used in the Roman Church. And lastly, a different ‘Benedictus’ is better known to musicians—the mass ordinary text which follows the ‘Sanctus’ text.

These were interesting to read about. I think it may be essential to study more stuff like this, as religious Latin texts greatly appeal to me for some reason. Also, I don’t know what a ‘Canticle’ is, but luckily, Parry contributes a complete discussion, which I will get to later as I move through the articles, as stated above.

No vocab words to note.

Arrangement - Hubert Parry

The next Parry article is on “Arrangement” or “Adaption.” Parry introduces the topic through a really cool analogy and then follows up with some history and musical examples. The analogy is so cool and eye-opening and sums up the main point of the article better than I can, so I am just going to quote it and follow up with some thoughts.

ARRANGEMENT, or ADAPTATION, is the musical counterpart of literary translation. Voices or instruments are as languages by which the thoughts or emotions of composers are made known to the world; and the object of arrangement is to make that which was written in one musical language intelligible in another.

The functions of the arranger and translator are similar; for instruments, like languages, are characterized by peculiar idioms and special aptitudes and deficiencies which call for critical ability and knowledge of corresponding modes of expression in dealing with them. But more than all, the most indispensable quality to both is a capacity to understand the work they have to deal with. For it is not enough to put note for note or word for word or even to find corresponding idioms. The meanings and values of words and notes are variable with their relative positions, and the choice of them demands appreciation of the work generally, as well as of the details of the materials of which it is composed. It demands, in fact, a certain correspondence of feeling with the original author in the mind of the arranger or translator. Authors have often been fortunate in having other great authors for their translators, but few have written their own works in more languages than one. Music has had the advantage of not only having arrangements by the greatest masters, but arrangements by them of their own works. Such cases ought to be the highest order of their kind, and if there are any things worth noting in the comparison between arrangements and originals they ought to be found there.

Two conclusions (for me) can be drawn from this: one, that studying and understanding the idioms of each instrument is vital in expanding and growing as a composer, and two, that arrangement is an excellent way of practicing writing for an instrument and solidifying its basic principles and idioms gathered through arrangement of my own, studies of scores, orchestration treatises, instrumentation treatises, and listening, of course.

One last interesting thing: I remember watching a BBC documentary on Holst and RVW where they mentioned (early on, I believe) that music written by German-speaking composers heavily dominated England’s concert halls and musical academia during the 19th century. And that composers like Holst and RVW (maybe Elgar, too) were trying to escape that and create uniquely British music. Anyway, the musical examples that Parry chooses after his linguistics analogy all come from German-speaking composers: Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms. It is also important to note that Parry heavily encouraged Holst and RVW to create a new British sound. It is interesting to see Parry simultaneously heavily influenced by German/Austrian music while gazing into the future of British music through Holst and RVW.

New Terms:

Conspicuous: standing out so as to be clearly visible or attracting notice or attention.

Diametric or Diametrically: completely opposed or characterized by opposite extremes.

Indispensable: absolutely necessary.

Bravura: great technical skill and brilliance shown in a performance or activity.

Mini Essay I: Bruckner - Mass No. 2, WAB 27

This harmonic analysis will focus on the opening phrase of the Kyrie in Bruckner’s Mass No. 2 in e minor.

Thus far, in my reading of Tchaikovsky’s Guide to the Practical Study of Harmony (1900), he has introduced two strategies for confirming a key. The first strategy is composing a cadence of the first group—this cadence contains the three functions found in tonal harmony: the tonic, sub-dominant, and dominant (resolving back to the tonic); it is this relationship that, to our ears, explicitly confirms the key we are in (Tchaikovsky pg. 77). The second strategy is the organ-point or pedal point which Tchaikovsky states is “nothing more than a further development of the ordinary cadence of the first group” (Tchaikovsky pg. 77).

An organ point is most often found at the end of a piece of music employed to establish the original key when a composer has modulated far away (a cadence of the first group may not suffice in this case). However, Tchaikovsky notes that it can also be found at the beginning or end of a piece of music. In this case, the organ point is usually composed on the tonic, is of short duration, and the first and last chords must harmonize with the bass (Tchaikovsky pg. 80). As seen in Fig.1, Bruckner’s passage seems to align with the guidelines recommended by Tchaikovsky.

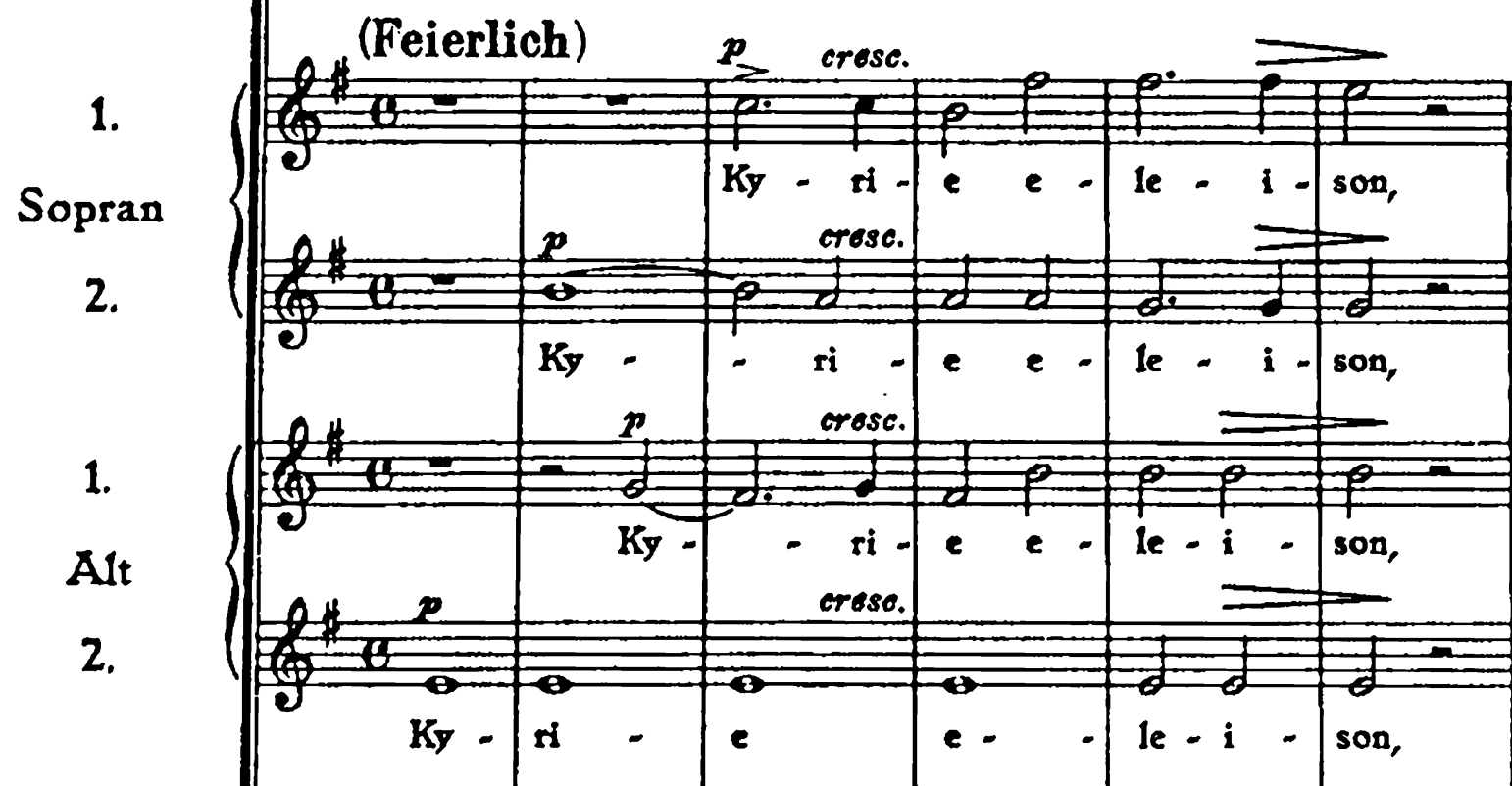

Fig. 1 - Opening Phrase (bars 1-6) of the Kyrie.

I interpret this first phrase (bars 1-6) as a highly decorated e-minor triad. Alto II holds the tonic pedal—alto I is just G, the third of the e-minor triad moving up to B, the 5th via accented neighbor tones. Soprano II moves from B the 5th down to G the third via 4-3 suspension (resolving in measure five). Soprano I is B moving to the tonic E decorated with an appoggiatura starting on the 3rd beat of measure four and resolving on the first beat of measure six.

Dissonance resolving is tension released—the effectiveness of the harmony in this opening phrase is not in harmonic movement but in the contrast of dissonance and consonance. The consonant e minor triads enclose the dissonant chords in measures four through six—the appoggiatura and its resolution, placed in the highest voice, heightens the feeling of closure—the silence that follows (half note rest) confirms the closure and the end of the phrase. Thus Bruckner is able to confirm the tonal center of e-minor without a perfect authentic cadence.

Tchaikovsky states at the beginning of the Second Section of his harmony treatise, “Suspensions, passing-notes, and changing notes greatly enhance the melodiousness of the voices; the simplest chord—succession can, by means of these attributes of voice-leading, be exalted to a high pitch of artistic and technical perfection” (Tchaikovsky pg.116). The opening of this mass encapsulates this quote.

The Practice of Music Part I

On Musical Style

It was not that he was afraid of war. But he did not like it.

— T.H. White, The Once and Future King.

In this free-writing exercise, I hope to process my thoughts and gain clarity on my artistic direction and musical curriculum moving forward. I want to start with ‘Musical Style.’

It seems impossible to separate this discussion from my experience interviewing as a Master’s candidate in Composition (as graduate school is a viable way of moving forward in this career path) at three prestigious conservatories: The Peabody Institute, Manhattan School of Music, and Mannes School of Music. I was unsurprisingly unsuccessful in securing a spot in these world-class programs, which has prompted me to reflect on what my next portfolio should look like. These reflections invariably lead back to the question of ‘Musical Style.’

I strongly disagree with the omnipresent pressure to create something entirely new. When placed as an expectation on students, it can be discouraging. However, I also reject the notion that all art is inherently unsafe—there is absolutely such a thing as safe art, and it is open to criticism. Navigating this space is mentally taxing: on one hand, developing a personal musical style should be an organic process—driven by an insatiable need to express oneself rather than an artificial attempt to mold one’s work into something academically novel. On the other hand, I do not want to box myself in by half-consciously composing within self-imposed limitations.

I think graduate school composition committees seem to be searching for students who demonstrate a clear artistic direction—whose portfolios attempt to express something personal and unique via a cohesive musical language. This necessitates a certain degree of technical understanding and craftsmanship, which must be evident both in the music and in the way the candidate articulates themselves in an interview. Regardless of these committees, this is something I recognize as crucial to strive for.

I think musical style is a conversation between the past and present. An artist, regardless of discipline, has the power to determine how to engage in this exchange—or whether to engage at all!

Alberti bass - Hubert Parry

Reading musical literature and working through theory treatises has become a source of calm amid a stressful time. I recently learned that Elgar found Hubert Parry’s contributions to the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians extremely helpful. I would also like to make Parry’s articles a part of my musical journey as they were for Elgar. I will go through his articles in alphabetical order.

Through these posts, I would like to define words or concepts I have not encountered before and summarize the article’s main point(s).

In this short article, Parry defines and briefly discusses the concept of Alberti bass. Alberti bass is a “formula of accompaniment” this formula consists of a pattern of four-note broken or arpeggiated chords. The pattern of notes is lowest-highest-middle-highest.

Parry mainly focuses on the music history behind Alberti bass rather than the theory of the concept. The name is derived from the 18th-century Venetian singer, keyboardist, and composer Dominico Alberti, who likely didn’t invent the formula, though certainly brought it into “undue” prominence (Parry doesn’t seem to like Alberti bass too much).

Parry wraps up the short article by discrediting Alberti concerning a couple of other musical concepts. I found Parry’s tone throughout kinda funny and definitely engaging.

New Words:

Enviable: an adjective that means desirable or admirable.

Injudiciously: showing very poor judgment; unwise. It means in a way that is not wise or sensible or in a way that is not appropriate in a particular situation.

Meretricious: apparently attractive but having, in reality, no value or integrity.

Edward Elgar by Diana M. McVeagh

This book has been incredibly illuminating. I wanted to devote a post to noting my observations and thoughts surrounding McVeagh’s analyses.

Elgar’s early cantatas are characterized by a composer who is still developing his technique. Despite this, I have always been drawn to them, especially The Black Night (1889-93). They are charged with this forward momentum, this energy that seemed, to my ear, unique. It was encouraging to read how remarkable it was that Elgar’s style developed quite early, was so distinctive, and remained consistent (192).

On Wagner, McVeagh states that “It cannot be disputed that without Wagner, Elgar would not have written in quite the way that he did, but in Elgar’s mature works, though much of their harmonic language he surely learnt from Wagner, there is no question of imitation” (197).

I want to outline some of the music theory I would like to hold on to. I am very interested in tonality but simultaneously loosening, pulling, or stretching functionality. Key area ambiguity and sudden or quick modulation (especially via sequence) are elements that really excite me. Briefly moving back to the Elgarian sequence, he often does not use chromatically descending or ascending sequences (by semitone), opting for larger intervals. Also, by treating a melody note in a sequence enharmonically, he modulates to any remote key he so chooses quickly and smoothly. I guess by taking advantage of the melodic cohesiveness a sequence provides. When writing out my own modulation exercises, I noticed that treating a tone as enharmonic, from the initial triad, is powerful in modulating to distant keys. To see it here in Elgar, as outlined by McVeagh, is very cool! Of course, this isn’t the only way Elgar modulates—even in a sequence. The common thread of all his modulations is that they are swift and fluid (196).

Harmonically, Elgar inherited from Wagner the full evocative vocabulary of chromaticism, decorated by suspensions, appoggiaturas, altered notes, and passing notes, often concurrently in several parts; of delayed resolutions, of free handling of high-powered chords, by which to express in dissonance from the most delicate to the most intense in every degree of romantic emotion (197). I love this quote from McVeagh. Further, Elgar also likes to slip one simple chord into an ornate chromatic progression (134). Also, if I remember correctly, elsewhere in the book, McVeagh states that Elgar also creates sublime music from the simplest of diatonic progressions. I believe the best example of this is his Variations on an Original Theme or Enigma Variations (1898-99).

McVeagh also discusses Elgar’s extreme sensitivity to verbal rhythm in The Dream of Gerontius (1900). When a vocal melody is composed in relation to the rhythm and structure of a text, it achieves a sublime naturalness that imparts a relationship between melody and word that, once heard, makes it impossible to dissociate the words from the music. Instead of fitting words after the fact or to an instrumental melody. This is an entirely new subject to me and led me to discover Rhythm and Harmony in Poetry and Music (1909) by George Lansing Raymond. I am really looking forward to reading this book.

“Psalms, Songs and Sonnets, Some Solemn, Others Joyful, Framed to the Life of the Words”

I am quickly noting Elgar's extensive use of the flattened seventh. I don’t understand this section and will ask Olsen for help on it.

Next counterpoint. Boy, this is important. Elgar’s chromatic and sometimes sliding harmony is prone to sag. However, this is saved by Elgar’s gift for counterpoint, in which “he constantly refreshes the repetitions of his themes by slipping them into them a new strand…It is through the themes sheer joy of life put forth spontaneously a new shoot” (201).

Elgar’s thematic development. I will quote here because all of this is so cool and exciting to me, and I want to take note of it here because I don’t own this book. “What he does in his developments is not to expound the properties of the material from his expositions or to set the main themes in contrast and conflict…or simply to reiterate them…but, like Sibelius, to take snatches and fragments and make of them something new” (204). “Elgar..flits from one to another, never stating but always hinting, shedding a momentary gleam of light here and there: he reveals relationships between apparently unconnected themes. Often chronological sequence is waived, as it is his habit not to display the resemblance at first, so that the recognition comes in the astonishment and then illumination. In fact, the moment of illumination is often not in the development…but in the recapitulation” (204). “This method of development is not confined to specific working-out sections or to movements in sonata form” (204). “Contrapuntal relationships are common. Sometimes a movement gives the impression that its themes must all move over the same harmonic ground at the same speed, so easily do they fit over each other, with never a tuck or bulge. In the second movement of the First Symphony, a tune from the trio lingers carelessly above the return of the scherzo theme, and the scherzo, on its second time round, puts its own two themes in double counterpoint. Always the choice of the exact moment to reveal such a relationship is masterly” (205). The end of The Apostles and Gerontius is strengthened by two leitmotifs, once heard separately, locked together with certainty (205). Elgar is also capable of more subtlety: “[In the last movement of the Second Symphony], forty-five bars before the end of the development, he presents a theme derived from the second subject. Eight bars later, he connects it with the first subject by [working out a new figure contrapuntally]. And then, at the recapitulation, as if to stress the relationship, he unexpectedly brings in a hint of it over the last bars of the first subject” (205).

“Elgar’s developments, indeed whole movements, have a continual reaching forward and back…Elgar’s development, then, is personal and characteristic of his mind. This partly explains why, though he used principles of systematic leitmotives in his oratorios, the results do not sound much like Wagner’s. For Wagner treated his leitmotives not only as symbols, modifying them as the dramatic action demanded, but also as musical subjects, developed in Beethoven’s manner and spun into a symphonic web. Such motival development is not Elgar’s most natural way. He frequently interlaces his leitmotives contrapuntally…his treatment of them is more like a mosaic: permutations of their order rather than modifications of individual ones.” (205-206).

So much to think about!!

Lastly, Elgar shows us the taking of mental images (In my case, I am most interested in images/emotions inspired by literature) and expressing them in music. This is a very open-ended concept and also provides so much to think about.

Thank you, Elgar. Your music has deeply touched me.

“I feel and don’t invent.”